Who decides who is a member of a community? Does the community decide who is, and who is not, “one of us”? Or is that decision imposed by an outside authority, dictating who must be admitted to the community and who must be excluded from it?

If a community is truly a free association of individuals, then it is a bottom-up process: the discretion as to whom to accept rests with the community. Criteria may be exclusively hereditary (as with some Native American tribes), or through some combination of birth and/or naturalization (American citizenship, or Jewish status).

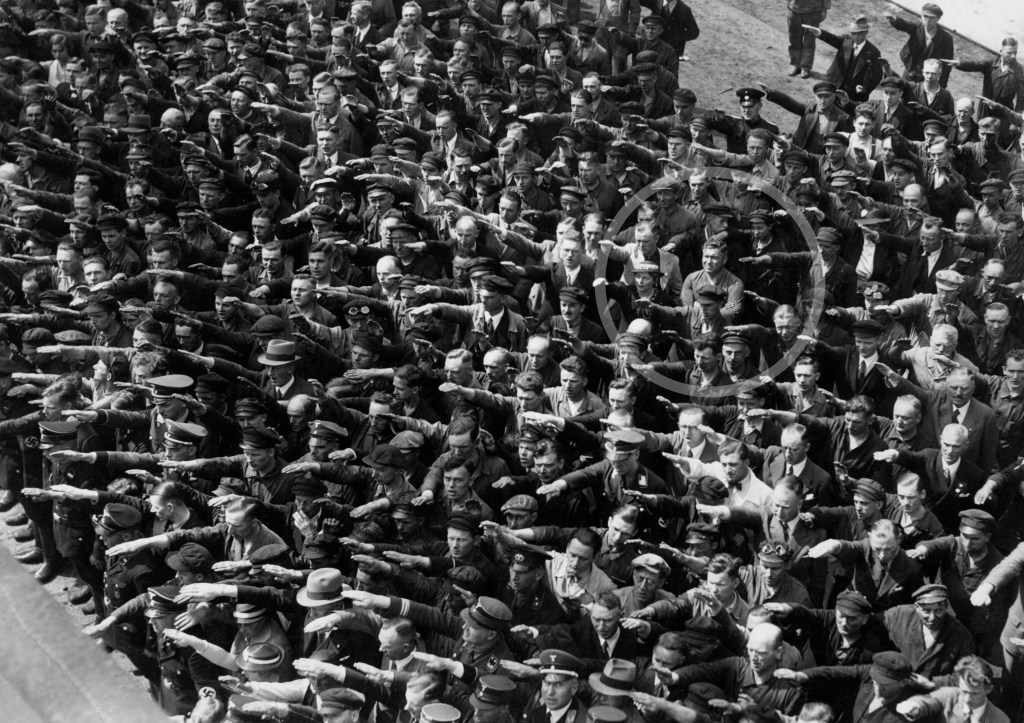

When an external power or authority seeks to commandeer the process of granting membership in a community, it is a safe bet that the ultimate goal is to destroy that community – and ultimately all free associations and communities – altogether. This is a top-down process and it is the hallmark of socialism.

Eve Barlow:

“In the trans community, socialist imposters are erasing the voices of genuine trans people who have lived their entire lives as well-adjusted, recovered and integrated trans people. These trans people reject extreme gender ideology, and rhetoric around non-binary, and live as transgendered people while simultaneously acknowledging facts about biological sex that don’t pose any threat to non-trans people. Similarly in the Jewish community, Marxist antizionist voices are drowning out the history, truth and ethnoreligious identity of regular Jewish people, and superimposing a globalization rhetoric that would wipe Israel off the map and bring an existential threat to the lives of every Jew in the diaspora.”

Membership in the human race entails membership in the community of men or of women; this is our oldest and most basic level of social organization. To affirm one’s gender as a woman or as a man is to affirm a basic commonality with half of the human race, and set oneself apart, in some way, from the other half. If a small portion of the general population (say about half a percent) experience a profound and persistent sense that they properly belong to the opposite gender – based on temperament, personality traits, and other intangibles – rather than what’s suggested by their biological sex, then this is a special case that can be addressed compassionately and constructively. That’s what good-faith transgender people and their allies in the non-trans world are seeking.

But in recent years, large numbers of people have been actively encouraged by the Left to identify as “transgender” for political reasons, ruining their lives and everybody else’s. This is further enforced by policies designed to demolish the safe spaces women have traditionally enjoyed on the playing field, in the locker room, and in the restroom. Leftist policies are actively aiding and abetting predators while punishing their victims. This is a top-down approach, and one that is calculatedly malevolent and destructive to human dignity and lives.

What the Left seeks is to eradicate gender entirely; to eradicate the communities of men and women, and ultimately to eradicate all communities, the better to soften up humanity to be crushed under the boot-heel of communism. It is another instance of the same tactic deployed against Jews and many others. To stand against it is to stand for the right of free people and communities. [431]