זְכֹר֙ יְמ֣וֹת עוֹלָ֔ם בִּ֖ינוּ שְׁנ֣וֹת דֹּֽר וָדֹ֑ר שְׁאַ֤ל אָבִ֨יךָ֙ וְיַגֵּ֔דְךָ זְקֵנֶ֖יךָ וְיֹֽאמְרוּ־לָֽךְ:

Remember the days of old; reflect upon the years of generations. Ask your father, and he will tell you; your elders, and they will inform you.

– Deuteronomy 32:7

In the story ‘The Slows’ by Gail HarEven (first published in Hebrew in 1999, and in English in 2009), the Slows are a population of humans who have resisted adopting AOG (Accelerated Offspring Growth) – a technology that produces fully-grown humans in a matter of months – and insist on bearing and raising children the old-fashioned way. The male narrator, who has taken an interest in the Slows, expresses revulsion at their way of life (which is presumably typical of his world) but also betrays suppressed feelings of attraction towards the Slow women, despite the “swollen protrusions on their chests and the general swelling of their bodies.”

In a world where nearly all living humans are the products of this “accelerated” growth, the legacy of the past seems something superfluous. The Slows, a dwindling population of holdouts against this technology, have become a relic no longer needed.

… “Those treaties were signed many generations ago. Things change,” I said, though I knew it was silly to get into an argument with one of them.

“My grandmother signed them.” …

In the dialog above, both parties are telling the truth: in the world of the story, the narrator has seen “many generations” elapse due to the advent of Accelerated Offspring Growth; but for the Slow woman and her ancestors who eschewed such technology, the same timespan connected grandmother and granddaughter.

It’s not accidental that this accelerated pace makes it easier for the narrator’s character to justify abrogating the old treaties – because after all, “things change”. The faster pace of life – and of the life cycle itself – makes the moral claim of the past on the present seem tenuous.

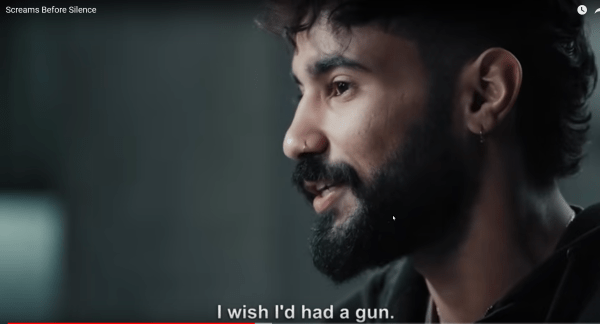

The short film adaptation differs from the print original in a few details (the “outsider” journalist is a woman in the screen version) but it is very good, and it’s faithful to the essentials of the story. There’s a wonderful scene (at 10:24) where the Slow woman playfully tosses an apple to the journalist – knowing that the other woman will be unable to catch it, never having developed those reflexes from playing catch as a child, since she never had a childhood.

There are some things we learn only by touch, or from experience, or from forming and sustaining an intimate bond with another human being – a parent, a child, a mate.

Most of what we know about the world, we learn from other people; and this includes the structures within which we organize our experience. These organizing structures include not only language (itself a collaborative and cumulative project), but also the nonverbal skills and processes that we learn from being around others.

It is the individual’s experience of living in a human body, with its sensations and passions and weaknesses; and it is the experience of having been born to humans, raised by humans, and challenged by humans. It is also the collective experience of humanity encoded in our cells, our relationships, and our culture.

The dystopian future of yesterday’s science fiction is the terrible reality of today’s news. We are living in a world where a clique of socially stunted psychopaths have used their control of technology and infrastructure to brainwash us into hating the very things that make us human: our childhoods, our sensations, our passions, our bodies with their swellings and their protrusions, our very lives.

We reclaim our humanity when we refuse the demands of the technocrats, embracing the humanity of our bodies and the continuity that connects us with our elders.